The FSU recently scored two significant victories in its ongoing campaign against speech-restricting Public Spaces Protection Orders (PSPOs). These are when a local authority decides to make certain speech illegal in its locality, often disregarding the legal protections for free speech.

As first reported by the Telegraph, Redbridge Council has agreed not to renew its current PSPO – which criminalises among other things behaviour which causes or is likely to cause harassment alarm or distress to another person’ – after the FSU wrote to them pointing out it was unlawful and threatening a judicial review.

Cumberland Council has also now said it will amend and extend its consultation on a new PSPO following a legal letter from the FSU – the council had been proposing to update its existing PSPO by introducing a ‘code of conduct’ for traders and street performers that said they must “always be courteous to members of the public” and must also be “calm and polite”.

These victories are welcome, but our campaign against the slow creep of these locale specific speech codes continues. Sadly, there are many other councils in England currently using PSPOs to introduce laws criminalising particular forms of speech.

So how did we get here?

PSPOs were first introduced into legislation via sections 59-75 of the Anti-Social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014 (‘the Act’). The original aim of these wide-ranging and flexible powers was to help local councils manage issues such as prostitution, begging, loitering, or drinking alcohol in specific areas, with a PSPO identifying a “restricted area” and either prohibiting or requiring specific things to be done there. Where breaches of PSPOs are identified, officials are empowered to impose a fixed-penalty fine of up to £100, or a court may impose a fine of £1,000 upon conviction.

Sections 59(2) and (3) of the Act outline two conditions that need to be met for a local authority to establish a PSPO (emphasis added):

(2) The first condition is that—

- activities carried on in a public place within the authority’s area have had a detrimental effect on the quality of life of those in the locality, or

- it is likely that activities will be carried on in a public place within that area and that they will have such an effect.

(3) The second condition is that the effect, or likely effect, of the activities—

- is, or is likely to be, of a persistent or continuing nature,

- is, or is likely to be, such as to make the activities unreasonable, and

- justifies the restrictions imposed by the notice.

Section 72 of the Act also requires local authorities to have “particular regard to the rights of freedom of expression and freedom of assembly set out in articles 10 and 11” of the European Convention on Human Rights. Of the PSPOs we have assessed so far, this appears more to be honoured in the breach. It seems that safety-minded officials tend to look with a jaundiced eye on any form of ‘free speech’ that may cause offence or ‘distress’.

Following criticism of how PSPOs were being implemented, the Home Office updated its statutory guidance in December 2017 to emphasise, inter alia, the need to ensure that relevant legal tests were being met to trigger the use of powers under the Act. (This guidance was further revised in January 2021, July 2022, and March 2023.)

In a section dealing with what should and shouldn’t be included in a PSPO, the latest version of the statutory guidance says (emphasis added):

As with all the anti-social behaviour powers, the council should give due regard to issues of proportionality: is the restriction proposed proportionate to the specific harm or nuisance that is being caused? Councils should ensure that the restrictions being introduced are reasonable and will prevent or reduce the detrimental effect continuing, occurring or recurring. In addition, councils should ensure that the Order is appropriately worded so that it targets the specific behaviour or activity that is causing nuisance or harm and thereby having a detrimental impact on others’ quality of life. Councils should also consider whether restrictions are required all year round or whether seasonal or time limited restrictions would meet the purpose.

It’s important to emphasise at this juncture that our concern is not with the PSPO per se. We recognise that they are a useful tool in the local council armoury and if properly used can lead to desirable outcomes for the community.

Our concern is one of ‘mission creep’, with the range of problems to which local authorities regard PSPOs as the answer, expanding in recent years to incorporate various forms of offensive but lawful speech and expression.

We are also concerned that local authorities are using orders, which should be limited in purpose and geographical reach, as a form of legislation used to govern the conduct of residents generally.

One of the main problems is that many of these PSPOs are criminalising conduct which causes ‘alarm or distress’ with no safeguards for free speech.

Why is that a problem? Let’s say you want to protest on the streets and unbeknown to you this causes someone ‘distress’. Unfortunately, according to some PSPO wordings, you might be liable, even if you didn’t intend it to and couldn’t have foreseen the ‘distress’ I would cause.

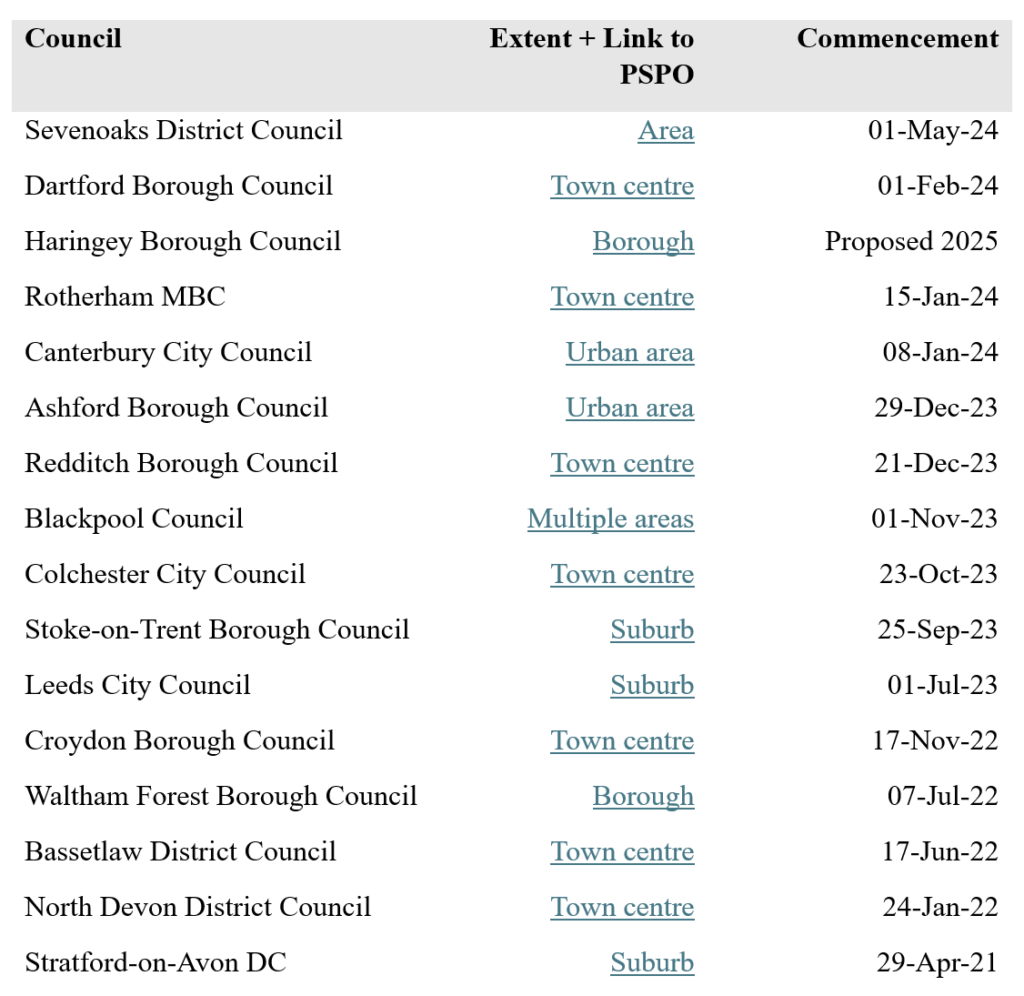

In total, the FSU has analysed PSPOs that are either in place or proposed across 16 local councils and found multiple instances where the conditions specified in the Act do not appear to have been satisfactorily met.

There are, for instance, regular references to words and phrases such as ‘swearing’, ‘shouting’, ‘insulting’, ‘obscene’ and/or ‘offensive’, as well as ill-defined behaviour terms such as ‘annoyance’, ‘nuisance’, ‘alarm’ and/or ‘distress’.

Did the local councils in question have “particular regard” to the Articles 10 and 11 rights of borough residents while formulating these vague, ill-defined speech terms? That’s a question we’ll be putting to them in our next round of legal letters.

What we’ve also discovered is that councils often fail to explain how these forms of behaviour and speech meet the conditions established by sections 59(2) and (3) of the Act for a PSPO to be established, namely, that the authority has evidence giving rise to reasonable grounds to believe that conduct is having a persistent and continuing detrimental effect on the quality of life of those in the locality.

Equally troubling is that PSPOs are now being established across overly extensive geographic areas, up to and including a whole borough. Under the Act a restricted area is defined as a public place within the authority’s area. We believe that any PSPO that expands to cover a whole borough, and not just to limited public places within it, would likely be in breach of this stipulation. The statutory guidance seems to agree, stating that ‘Public Spaces Protection Orders are intended to deal with a particular nuisance or problem in a specific area’ (emphasis added).

A PSPO that imposes a rule of conduct, backed by criminal sanction, across an entire borough, goes beyond the proper scope of an order, which is an executive act by a local authority, into the realm of legislation. It is important to note that all of the PSPOs we have looked at far exceed the restrictions Parliament chose to impose on conduct causing ‘harassment, alarm and distress’ when it enacted the Public Order Act 1986. It is inappropriate – perhaps even unconstitutional – for councils to use their powers to create their own bespoke criminal law, with disregard for the safeguards on liberty imposed by Parliament.

The full list of councils that the FSU has analysed to date, including a link to the relevant PSPO, is set out in the table below.

While we continue to write to these local authorities, we also want to hear from anyone who may be aware of PSPOs – again, either in place or proposed – that they believe could lead to the suppression of free expression, especially if you are located within or close to the relevant restricted area.

There is also another way for people to join the fight against these instruments.

Section 60 of the Act states that a PSPO may not have effect for a period of more than three years, unless extended. In addition, a local authority must carry out a consultation upon the introduction or extension of a PSPO which should include “whatever community representatives the local authority thinks it appropriate to consult” (section 72(4)(b)).

According to the Local Government Association’s guidance for local councils, “alongside residents, users of the public space, and those likely to be directly affected by the restrictions, this might include residents’ associations, local businesses, commissioned service providers, charities and relevant interest groups”.

The consultation stage does, therefore, give residents and business owners an important opportunity to shape the final form of any proposed PSPO from a free speech perspective, so if your local authority is currently consulting about a PSPO make sure you have your say.