Police are recording more non-crime hate incidents (NCHIs) than last year despite a crackdown on the practice, according to an analysis of official data by the Free Speech Union (FSU). (The Telegraph covered the story here).

In 2014, the College of Policing (CoP) came up with the concept of the NCHI in its Hate Crime Operational Guidance. As defined in this document, an NCHI is any incident perceived by the victim or any bystanders to be motivated by hostility or prejudice to the victim based on a ‘protected’ characteristic (race or perceived race, religion or perceived religion, and so on).

“Perceived” is the operative word here, since as the guidance goes on to note: “The victim does not have to justify or provide evidence of their belief, and police officers or staff should not directly challenge this perception. Evidence of the hostility is not required.”

In other words, according to the CoP, the recording threshold for an NCHI is that someone had taken subjective offence to something perfectly lawful that someone else has said or posted online, whether it’s directed at them or not.

Things appeared to take a turn for the better when Suella Braverman, the former home secretary, last year told police they should use their common sense, and only log reports of alleged ‘hate incidents’ that were below the criminal threshold if there was a serious risk of harm and not just because someone was offended.

Under Ms Braverman’s leadership, the Non-Crime Hate Incidents: Code of Practice on the Recording and Retention of Personal Data (‘the Code’) was issued by the Home Office in June 2023 pursuant to the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022.

However, police figures for 30 of the 43 forces in England and Wales, obtained by the FSU through Freedom of Information (FoI) laws, showed that the number of NCHIs actually increased by 0.4 per cent from 11,642 in the year to June 2023 to 11,690 in the year to 2024.

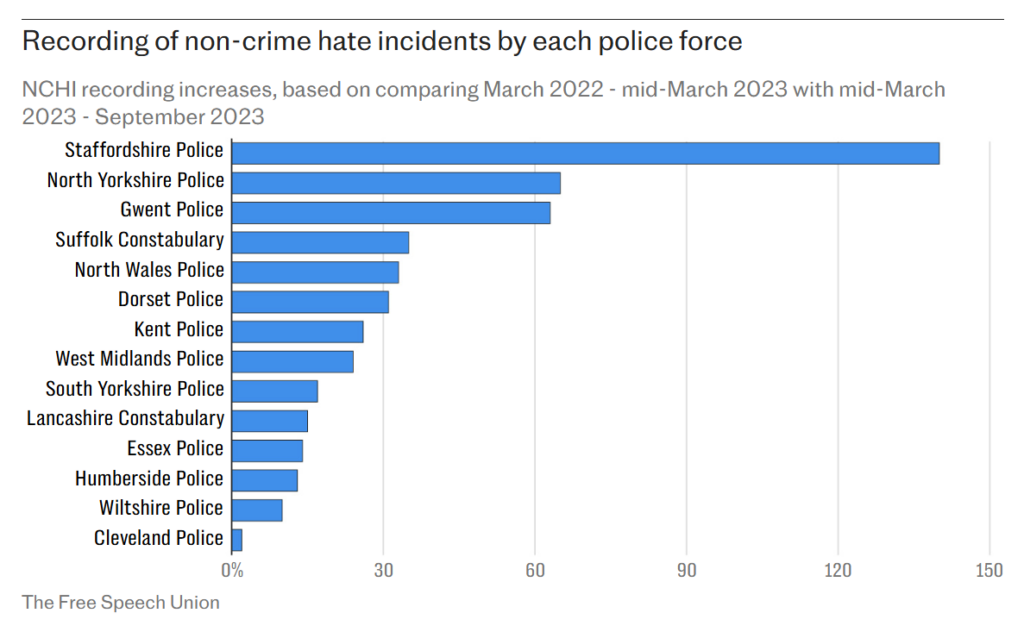

The data revealed some forces recorded big increases, including Staffordshire (140 per cent), North Yorkshire (65 per cent), Gwent (63 per cent), Suffolk (35 per cent) and North Wales (33 per cent).

Speaking to the Telegraph about this surprise increase in the total number of recorded NCHIs, FSU General Secretary Toby Young suggested the “message had not got through” to police forces in England and Wales that the recording of such incidents represented an interference with people’s free speech.

He also pointed out that the rise could undermine moves by the new Home Secretary, Yvette Cooper, to toughen hate crime laws – the Labour minister’s claim is that Ms Braverman’s Code has contributed to a drop off in recording of NCHIs, specifically in relation to anti-Semitism and Islamophobia.

Toby said it would weaken the argument that the abuse had risen because of this alleged decline in recorded NCHIs. Alternatively, the rise could mean police were already logging such incidents following the Hamas terror attack on October 7th, he added.

As first reported by The Telegraph, Ms Cooper is “committed to reversing the Tories’ decision to downgrade the monitoring of NCHIs, specifically in relation to anti-Semitism and Islamophobia, so they can be logged by police”.

But the underlying premise here simply isn’t true. Ms Braverman’s Code never prevented the recording of NCHIs. Rather, it just put the recording and retention of NCHIs on a lawful footing.

Under Ms Braverman’s existing statutory guidance, there are two subsets of NCHI record: those that include the personal data of the alleged perpetrator, and those that only include locational data. Both subsets require a perception of hostility or prejudice, and that the recording police officer believes this hostility to be intentional.

However, personal data regarding the alleged perpetrator may only be included if the event also presents “a real risk of significant harm to individuals or groups with a particular characteristic(s) and/or a real risk that a future criminal offence may be committed against individuals or groups with a particular characteristic(s)”.

🚨 BREAKING: We've written to the Home Secretary Yvette Cooper threatening to take her to the High Court over her plan to force police officers to record more 'non-crime hate incidents' (NCHIs)!https://t.co/DPCh2HSpOW

— The Free Speech Union (@SpeechUnion) September 1, 2024

👊 We're not prepared to stand idly by while this Labour… pic.twitter.com/QGmrXU2lRj

As the Code points out, in many cases where these risks don’t exist, location data “may be all that is required in order to identify patterns of behaviour, identity incident hot spots, or monitor community tensions”.

So is the Home Office planning to take us back to the bad old days when the subjective perception of “hatred” was enough to have your name and address logged in a police database?

What we know is that back in March, Ms Cooper, the then Shadow Home Secretary, told the Telegraph that there needed to be a “new and effective hate crime action plan”, which would include “reversing the current presumption, specifically for antisemitic and Islamophobic hate, that personal data on perpetrators of such hate should only be recorded by police where there is a “real risk” of significant harm or future criminal offending”.

What Ms Cooper appears not to realise is that the reason for the “current presumption” was to bring the recording and retention of NCHIs into line with the law – particularly Article 10 of the ECHR – and if she “reverses” it, the likelihood is she would be encouraging the police to break the law.

The guidance was introduced after Harry Miller, a retired policeman, took the College of Policing to court over its hate crime operational guidance in 2021.

Miller was reported to the police for transphobia in 2019 after tweeting a piece of feminist doggerel that took the Mickey out of trans women. A police officer visited his house, told him to “check his thinking”, and an NCHI was recorded against his name.

He challenged Humberside Police’s decision to record the incident as a “non-crime hate incident” and took his case against Humberside Police and the College of Policing to the High Court. Harry then took the College of Policing to the Court of Appeal to challenge its Hate Crime Operational Guidance.

In a victory for free speech, the court ruled that the recording of NCHIs on the scale it was taking place was an unlawful interference in freedom of speech and a breach of Article 10 of the ECHR.

Following that victory, the FSU worked with Lord Moylan and other peers to secure an amendment to the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill 2022 that gave the Home Secretary the option of placing the recording of NCHIs and the retention of the data on a statutory footing, governed by a Code of Practice approved by Parliament instead of the say-so of the College of Policing.

Then, in March 2023, the then Home Secretary Suella Braverman availed herself of that option, with the Home Office publishing its Code on the reporting and recording of NCHIs. In accordance with Miller v The College of Policing [2021] EWCA Civ 1926, this guidance required police to exercise their common sense and be mindful of people’s right to free speech before recording an NCHI.

As per the Code: “All efforts should be made [by officers] to avoid a chilling effect on free speech (including, but not limited to, lawful debate, humour, satire and personally held views).”

It continued: “Even where the speech is potentially offensive, a person has the right to express personally-held views in a lawful manner. This includes the right to engage in legitimate debate on political speech or speech discussing political or social issues where this is likely to be strong differences of opinion.”

But of course if the data uncovered by the FSU is anything to go by, Labour’s new Home Secretary may not need to spend too long watering down this existing “use your common sense” Code, since most police forces in England and Wales appear never to have adopted it in the first place.