Academic freedom in the UK has deteriorated for the ninth year in a row, according to the latest update to the Academic Freedom Index (AFI).

The UK is one of just three Western countries to feature on the AFI’s list of places where academic freedom has substantially worsened since 1973. The other countries to share this dubious distinction are Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Hong Kong, India, Laos, the Netherlands, Turkey and the US.

The UK also scored lower than any of its western European neighbours over the past 10 years, many of which claimed spots among the top 10 per cent, including Italy, Germany, Spain and Portugal.

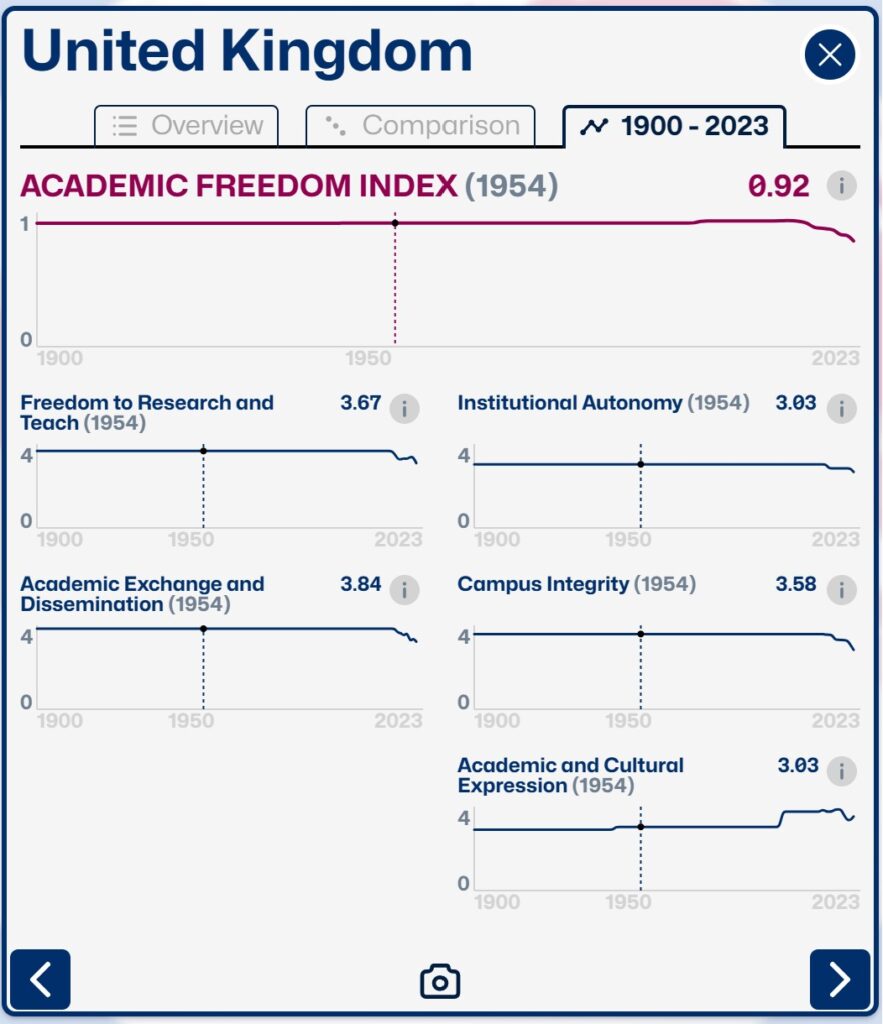

To determine levels of academic freedom, AFI researchers draw on assessments made by 2,329 country experts from around the world. The assessments are made regarding “undue interference” by non-academic actors (e.g., politicians, externally appointed university management, activist groups) across five separate indicators: freedom to research and teach; freedom of academic exchange and dissemination; the institutional autonomy of universities; campus integrity; and freedom of academic and cultural expression.

Across each indicator, the level of academic freedom is ranked on a scale from 1 (“completely restricted”) to 4 (“fully free”).

Data on those five indicators are then combined to produce an aggregate score for each country’s overall level of academic freedom, where values range from 0 (the lowest level of academic freedom) to 1 (the highest level).

Between 1900 and 1999, the UK’s overall index score remains steady at 0.92, and actually increases between 2000 and 2014, to 0.94. However, it has decreased every year since, and in 2023 stood at 0.79.

This dip in the UK’s index score is due to a decline across each of the AFI’s five separate indicators, with the sharpest falls coming in relation to ‘academic exchange and dissemination’ – down from 3.84 in 2015 to 3.22 in 2023 (–16% per cent) – and ‘campus integrity’ – down from 3.58 to just 2.81 (–21% per cent).

Academic exchange is assessed via the question “To what extent are scholars free to exchange and communicate research ideas and findings?”, while campus integrity is assessed via the question, “To what extent are campuses free from politically motivated surveillance or security infringements?”.

Speaking to the THE about the latest update to the Index, AFI researcher Lars Lott said restrictions on academic freedom make advancing knowledge difficult and “undermine universities’ educational role in society by placing ideology, economic or political interests over the pursuit of academic knowledge”.

These are grim, but not particularly surprising data.

For instance, a survey carried out by the Office for Students (OfS) during academic year 2021-22, found that a record number of speakers and events had been rejected on campuses in England and Wales. Out of 19,407 external speaker requests or events during that 12-month period, 193 were rejected, compared with 94 in 2019-20, 141 in 2018-19 and 53 in 2017-18.

During the period covered by the OfS study, the FSU also helped hundreds of students and academics, all of whom had got into trouble for expressing nonconformist views or pushing back against ideological orthodoxy on campus, whether by refusing to do unconscious bias training, criticising their university’s links with Stonewall, objecting to the decolonisation of the curriculum, or daring to point out that George Floyd had a criminal record.

Then there’s the countless other incidents that occur but never come to the attention of organisations like the FSU, and must surely have a ‘chilling’ effect on the actions of all who come to hear of them through the academic grapevine.

As the then Reader in Philosophy at Cambridge University, and now OfS Director for Freedom of Speech and Academic Freedom, Arif Ahmed, attested in a piece for Spiked: “I have attended conferences on the Gender Recognition Act that have had to be held in secret locations on university premises, unadvertised, with a closed guest list. I have met academics who live in daily fear of violence for expressing a widely held scepticism about Stonewall – and their universities do nothing to protect them. I know of 18-year-olds being ostracised within weeks of starting at university because someone dug up something they had written questioning this or that orthodoxy.”

Understood in this broader context, it is, as Dr Ahmed concluded, “virtually impossible to deny with a straight face that there is a free-speech problem at universities”.